Abstract

Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) play a critical role in the supply chain management of their companies. This work explores how SMEs should identify and manage their outsourcing activities to increase and maintain their competitive advantages through innovation in new products, processes, business models, organizational structures, and services. Using an exploratory case study methodology, this study aimed to illuminate the strategies and challenges associated with strategic outsourcing (SO) in SMEs operating within Slovakia’s manufacturing sector. Through a careful selection of cases comprising high-performing and average-performing companies and a comprehensive data collection approach involving structured interviews, this work captured rich insights into the dynamics of SO management. This study’s findings revealed converging and diverging approaches to SO decision steps among SMEs in Slovakia. By presenting the findings through a systematic analysis framework, this research offers valuable insights for SME owners, managers, and stakeholders seeking to enhance their SO practices. This research offers actionable insights for SMEs striving to navigate the evolving landscape of global competition and innovation.

Keywords: SMEs, Supply Chain Management, Strategic Outsourcing, Comparative Analysis, Decision Making, Case Study

An updated version of part 1 of Ümit Güfte PEKÖZ Master’s Thesis, „Strategic Outsourcing Decision Model“.

Peköz, Ü. G. (2011). Strategic outsourcing decision model [Master Thesis, Technische Universität Wien]. reposiTUm. https://resolver.obvsg.at/urn:nbn:at:at-ubtuw:1-50533; WU Executive Academy.

Introduction

Today’s economy is influenced by globalization and shorter product life cycles, leading to a greater emphasis on faster time to market and increased pressure on companies to deliver quicker Return on Investment (ROI) for their investors (Harland et al. 2005) (Quélin & Duhamel 2003) (Gonzalez et al. 2005). In this context, strategic outsourcing decisions are not just a trend but necessary, empowering European and Western companies to remain competitive (Quélin & Duhamel 2003). According to Lewin and Peeters (2006), 97% of companies consider cost reduction the primary motivation behind outsourcing decisions, a powerful tool in their arsenal to navigate global market pressures. In today’s rapidly changing business environment, nearly everyone has access to the outsourcing activities necessary to gain a competitive advantage quickly. When a company outsources, its competitors quickly catch up, reducing the competitive gap. As a result, companies need to create unique values and differentiating factors. In this new business environment, the difference between winners and losers will be determined by the correct selection of activities to be outsourced, the collaboration and networking maintained throughout the outsourcing activity, and the use of strategic partnerships to create new knowledge and know-how (Hamel et al., 1989; Porter, 1996).

This thesis will illustrate the importance of SMEs choosing the right activities to outsource to maintain their market position and stay competitive. More than just a cost-saving measure, outsourcing can catalyze innovation, helping SMEs create unique values and differentiating factors. This work will examine how SMEs should identify and manage their outsourcing activities to increase and maintain their competitive advantages through innovation in new products, processes, business models, organizational structures, and services.

In this paper, I aim to explore the key decision-making and management steps for successful long-term outsourcing. This paper aims to contribute to the success of SMEs by providing a framework for outsourcing management. With this framework, SME managers can better understand outsourcing projects as opportunities for collaboration and partnership rather than just buyer-supplier relationships.

The rationale behind the work

The importance of strategic outsourcing (SO) for companies is mentioned multiple times in the literature (Elango, 2008; Quélin & Duhamel, 2003). In today’s business environment, companies cannot compete without it (Harland et al., 2005). It is suggested that no one can do it alone but only through partnerships (Hamel et al., 1989). Furthermore, works explain how companies can access external knowledge through SO, which can otherwise take years to accumulate (Baloh et al., 2008). Due to the general acceptance of these findings, SO partnerships are unavoidable.

Companies are also exposed to risks when they are pressured to implement supplier outsourcing (SO). These risks can lead to significant problems for companies and even cause them to exit the industry. Quelin (2003) has identified some risks, such as dependence on the supplier, loss of know-how, and service providers‘ lack of capabilities to meet changing requirements. In my experience, the potential risk of losing one’s knowledge base and know-how is the most threatening for companies.

Before starting my MBA studies, I worked in a service center for several years for an IT company in Bratislava. During this time, I was involved in various SO projects, participating in phases such as activity transfer, change management, and handing over activities back to the Mother Company. Losing one’s own knowledge base can lead to long-term problems as the company becomes more reliant on its suppliers to adapt to changing market trends and customer needs. To maintain sustainable competitiveness, it’s essential to determine the extent to which a company can outsource activities to external partners with better capabilities or knowledge without losing control over these activities (Quélin & Duhamel, 2003) (Becker & Zirpoli, 2011).

Recently, I encountered numerous situations where a multinational IT company, with billions of dollars in resources and extensive experience in supply chain management, faced serious issues in managing its supply chain operations both as a supplier and as an outsourcer. For instance, when my company took on new responsibilities, we often encountered problems that the partner company had not informed us about in procedure documents or training meetings. This lack of information led to escalated problems, affecting customer satisfaction and our reputation as a supplier, and resulted in resource waste in some cases. If large corporations with substantial resources and extensive knowledge face such challenges, how do small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) manage in this environment? SMEs have limited assets and capital and may lack extensive experience in supply chain management. Yet, outsourcing is crucial for them to stay competitive in pricing and gain access to new products and resources. However, while outsourcing can enhance competitiveness in the short term, inexperienced SMEs often face long-term negative consequences, such as loss of core knowledge and capabilities.

After reviewing the existing literature and drawing from my own experience, I have centered my work around the following question: How can we develop a model to identify the differences in SME management between successful and average-performing SMEs to assist SMEs in their SO practices?

Theoretical Framework

Many researchers agree on several common steps companies use in SO management, usually starting with identifying a niche to outsource. Companies analyze their competitiveness and capabilities in the market and evaluate options for covering any gaps found. If a company decides it cannot cover the gap within the firm, strategic outsourcing is seen as a good option for acquiring resources (Hamel et al., 1989; Quélin & Duhamel, 2003). Previous researchers have identified the choice of outsourcing partner as a key step to success (Rundquist, 2003) and have raised questions regarding the best approach to activity transfer so that it does not affect performance or consumer satisfaction (Lorber, 2007). Researchers highlight similar concerns about performance monitoring in SO activity (Kelley & Jude, 2005). Once the activity has reached a stable state, what further collaboration activities are done between partners, and how can companies transfer the knowledge generated by outsourcing partners to create new products and solutions? (Hamel et al., 1989; Marques & Ferreira, 2009). It is interested in how companies monitor the market and adapt to changing customer preferences during and after outsourcing. Staying aware of market dynamics and observing surroundings to understand customer needs is crucial. This helps identify emerging technologies that can address customer needs in new ways. Failure to adapt to changing needs may jeopardize a company’s survival when new technologies become available.

Conceptual Framework and Assumptions

I will use a comparative case study as my methodology (Yin 2003). The study will involve collecting primary data through structured interviews with SME owners and decision-makers. I plan to conduct interviews with a total of 6 companies, divided into two groups: high-performing SME companies and average-performing companies, in line with industry standards.

The interviews will be based on 5 scale-structured questionnaires with room for comments. I will focus more on qualitative data rather than quantitative data. After collecting the information, I will evaluate and analyze it through comparative analyses. Using knowledge gained from previous studies of SO management and my own experience, I have identified the 7 main stages in SO management. I am creating a model around supply chain outsourcing (SO) to identify differences in companies‘ approaches and variations in performance. The research assumes that all companies involved practice outsourcing and gain short-term advantages from this arrangement. It also assumes that SMEs carry out their outsourcing activities in various ways, with some common approaches causing competitive disadvantages in the long term.

Statement of the Problem

In both literature and practice, outsourcing is often seen as an attractive option for companies due to its financial advantages and potential to fill competitive gaps. However, companies may lose competitiveness and market share long-term due to a lack of internal knowledge. This can lead to an inability to respond to customer needs, market trends, and changing technologies. This work aims to develop a decision model for companies to help them avoid these pitfalls in strategic outsourcing management.

The companies involved in this research are small and have limited resources, but they are highly motivated to compete globally, particularly in Europe. Without a good understanding of effective approaches to outsourcing, these companies risk significant long-term disadvantages due to their outsourcing activities, including the loss of the company’s knowledge base and a loss of flexibility.

How can small and medium-sized enterprise (SME) owners and managers, in their strategic outsourcing decisions, identify and manage the right outsourcing activities and collaborate with their outsourcing partners to generate new knowledge for increased innovation and competitiveness?“

To answer this question, I will delve deeper into the decision-making process regarding what and how to outsource, focusing on knowledge generation and innovative competitiveness. When collecting data from the field, I will seek to address the following stages of strategic outsourcing (SO) decision-making to gain a better understanding of current SO management practices:

- How do small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) choose which activities to outsource?

- What are their initial expectations from the outsourcing activity?

- How do they select and partner with external entities?

- How do they transfer activities and knowledge between parties?

- What aspects do they control during the activities?

- How do they leverage the opportunity to learn from the partnership?

- How do they monitor market dynamics and emerging knowledge?

Which of these stages in outsourcing management contributes the most to a successful company? Once we understand how successful companies manage their outsourcing processes, we can identify the key decision steps and raise awareness among companies. This will enable them to make better decisions and comprehend the long-term consequences of outsourcing.

Importance of the Study

Although outsourcing presents many short-term advantages, it also brings long-term risks. The top 3 risks Quelin (2003) identified are dependence on the outsourcing supplier, loss of know-how, and the supplier’s reliability to evolve together with the outsourcer. Similar risks are identified at the organizational, sector, and national levels by Harland (2005). I found the risks identified in both studies devastating to SME companies with limited resources, as they have no second chance to apply lessons learned from unsuccessful outsourcing practices.

A comparison of interview findings will identify activities and key decision points that contribute significantly to an SME’s performance.

The study’s results will help us assist SME companies stay competitive in the long term by raising awareness of outsourcing risks and supporting decisions by identifying the key factors contributing to top performance.

Literature Review

This section, which summarizes the existing theories on the advantages and risks of outsourcing, is not just an academic exercise. It has practical implications for companies, as it enables them to enhance competitiveness, concentrate on core competencies, and achieve short-term cost benefits. The insights from this section will guide our research and provide a context for our findings.

According to Harland, outsourcing can release assets and reduce costs in the immediate financial period. Organizations that outsource parts of their in-house operations have reported significant savings in operational and capital costs (Rimmer, 1991; Hendry, 1995; Uttley, 1993). Laugen et al. (2005) identified a correlation between outsourcing best practices and high-performing companies, which is attributed to transaction cost economics (TCE) underlying make-or-buy decisions (Ellram & Billington, 2001). Other benefits of outsourcing are evident in the literature on strategic management, operations management, purchasing and supply, and innovation. For instance, Teece’s (1986) concept of „complementary assets“ highlights the benefits of partnering with organizations whose resource bases complement one’s own (Mowery, 1988; Doz, 1988). Some scholars suggest that outsourcing improves flexibility to adapt to changing business conditions and demand for products, services, and technologies (Greaver, 1999). Other outcomes, such as improved credibility and image, greater workforce flexibility, and avoiding being locked into specific assets and technologies, are more challenging to measure. There is limited research to guide managers on how to measure outsourcing performance (Harland et al., 2005).

The following motivations for outsourcing (SO) are also identified in work by Quélin & Duhamel (2003), along with the supporting literature:

- Companies practice SO to reduce operational costs (Lacity and Hirschheim (1993b); McFarlan and Nolan (1995); Barthe’lemy and Geyer (2000); Kakabadse and Kakabadse (2002) cited by (Quélin & Duhamel 2003).

- To focus on core competencies (Quinn and Hilmer (1994); Saunders et al. (1997); Alexander and Young (1996b); Kakabadse and Kakabadse (2002) cited by (Quélin & Duhamel 2003), to reduce capital invested (McFarlan and Nolan (1995); Kakabadse and Kakabadse (2002).

- To improve measurability of costs (Barthe’lemy and Geyer (2000) cited by (Quélin & Duhamel 2003).

- To gain access to external competencies and to improve quality (Quinn and Hilmer (1994); McFarlan and Nolan (1995); Kakabadse and Kakabadse (2002) cited by (Quélin & Duhamel 2003).

- To transform fixed costs into variable costs (Alexander and Young (1996a) cited by (Quélin & Duhamel 2003).

- To regain control over internal departments (Lacity and Hirschheim (1993a); Alexander and Young (1996a) cited by (Quélin & Duhamel 2003).

These studies generally agree that companies benefit from SO in the short term due to the challenges created by globalization, knowledge division, and widespread manufacturing capabilities. However, these studies also identify several risks involved in outsourcing that can ultimately damage a company’s competitiveness.

Harland (2005) comprehensively analyzed the risks associated with outsourcing (SO). According to the analysis, some organizations fail to realize the expected benefits of outsourcing. For instance, a report cited in Lonsdale (1999) and McIvor (2000) indicated that only 5 percent of surveyed companies achieved significant benefits from outsourcing. Lonsdale (1999) and Cox (1996) highlighted reasons for this, such as focusing on short-term benefits, lacking formal decision-making processes for outsourcing, including medium and long-term cost-benefit analyses, and facing increased complexity in the total supply network. Marshall (2001) concluded that insufficient attention had been paid to managing the outsourced activity in general and that outsourcers do not receive guidance on approaching the task.

Additionally, Quélin and Duhamel (2003) identified the risks of outsourcing based on the literature and previous studies.

I have noted the following risks identified in the SO:

- Dependence on the supplier

- Hidden costs

- Loss of know-how

- Service provider’s lack of necessary capabilities

- Social risk

These findings align with our experience in the SO practices of an IT company outsourcing center in Bratislava. They have led us to the following thesis question:

How can SME owners and managers identify and manage suitable outsourcing activities and collaborate with their SO partners to generate new knowledge for increasing innovation and competitiveness?

Identified Steps in Strategic Outsourcing Management

We conducted comparative case studies between successful and average-performing SMEs to identify key differences in SO (outsourcing) practices. To do this, we developed a decision model covering the steps involved in SO decision-making. we aimed to create a tool to compare companies‘ managerial approaches to outsourcing practices and identify the key steps in the outsourcing process.

A review of the literature suggests that there are seven steps involved in a company’s outsourcing management:

- Identifying SO activities

- Evaluating SO activities

- Selecting suppliers

- Transferring activities

- Controlling and managing SO contracts

- Learning and knowledge transfer

- Monitoring market dynamics and emerging innovations

I will present a model based on these 7 steps, which can be used by SME managers/owners to analyze their outsourcing practices. This model aims to broadly reflect many aspects of outsourcing decision-making, as mentioned in the literature.

First, companies must identify the activity they want to outsource and clearly define their goals. This will help in evaluating the outsourcing project for approval. If the activity is approved, the company should select the right supplier.

Next is a transition period, during which knowledge is partially transferred to the outsourcing partner, and criteria are set to smoothen the process. Once the outsourced activities have been transferred, companies usually identify gaps in the supplier’s ability to meet existing quality standards and develop new solutions that can be integrated into existing products and business lines.

After the activities have been transferred, companies must establish a process to control the outsourced activity. Setting the correct performance indicators is crucial for outsourcing success (Kelley & Jude, 2005; Kathleen 1995; Lorber 2007, Michael A. Stanko et al. 2009).

Some studies also highlight the need for outsourcing companies to learn from their partners and generate new knowledge to stay competitive (Hamel et al., 1989; Porter 1996, as cited by Marques 2009). Once outsourcing reaches a stable state, it is vital for companies to keep track of market trends and changing customer preferences to maintain their current customer base and access new market segments.

The following section will provide detailed information about each of these decision steps. This work aims to create a decision model and then apply it to companies to demonstrate the steps that contribute to the success of companies using outsourcing.

SO Activity Identification

Elango (2008) emphasizes that in today’s competitive world, identifying activities to outsource is crucial for maintaining competitiveness. Since any company can carry out standard activities, the difference between highly successful and average-performing companies can be bridged by adopting successful companies‘ approach to outsourcing management and activity identification. Elango proposes that companies gain a competitive advantage by identifying their core activities and the knowledge that cannot be documented but is essential to enhancing their core operations. To achieve this, companies can utilize an „outsourcing matrix“ to identify activities suitable for outsourcing.

This matrix can be seen in Table 1.

| Table 1: Outsourcing Matrix, adapted from a work by B. Elango, 2008 | |||

| Strategic Importance | |||

| Non-Core | Core | ||

| Outsourcing Role | Supplementary | Cell 1

Efficiency (e.g., Record-Keeping, Web-Site Maintenance) | |

| Complementary | Cell 2

Synergy & Legitimacy (e.g., Joint Marketing, Financial Reporting) | Cell 3

Core-Enhancing (e.g., Research) | |

The outsourcing matrix proposed by Elango categorizes business activities into four groups based on whether they are supplementary or complementary, core or non-core. If an activity is supplementary and non-core, it should be outsourced. If an activity is complementary but non-core, outsourcing can support it, such as in accounting or marketing activities. After this classification, companies must determine if the activity is strategically core or non-core. Core activities are the value-adding activities within the firm’s core competence, while non-core activities are those outside the core competence.

Hamel et al. (1989) warn that misidentifying activities for outsourcing can harm a company’s long-term competitiveness, even though outsourcing may initially seem like the only option to cover competitive gaps. Their main concern is the transfer of knowledge to suppliers, which gives them access to the outsourcing companies‘ own markets. This is particularly problematic in companies with multiple departments with different yearly targets, each of which might be using outsourcing practices without understanding the cumulative effect of such activities (Hamel et al., 1989).

The following section will discuss the process of identifying outsourcing opportunities and explore the question of which individuals in an organization are best suited to make selections for outsourcing activities and how they should make these selections.

Management Functions in place to make SO decisions

The general belief is that small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) have few management layers, allowing for effective communication between decision-makers. However, in some cases, line managers or remote plant managers are authorized to make decisions about their daily operations without consulting others. While this may streamline operations and boost productivity, it can also create potential problems in supply chain management. If outsourcing decisions are made independently rather than through coordinated efforts, the knowledge and activities entrusted to other companies can accumulate and threaten the company (Hamel et al., 1989). Therefore, SMEs require a centralized supply chain outsourcing (SO) decision unit directly connected to the strategic decision committee to prevent such situations. This will enable top management to see the bigger picture and avoid getting lost in the details. It is also concluded that having a centralized SO decision unit is crucial (Hamel et al., 1989; Harland et al., 2005).

Understanding Core Competencies

In order to understand its position in the market and the unique value it offers to customers, an SME should first identify its core competencies. This can be done by mapping out its processes and revealing areas for potential improvement even before embarking on a strategic outsourcing (SO) project. It is important for the SME to carefully analyze whether an activity is within its core competency, where it resides, whether it involves implicit or explicit knowledge, if this knowledge is already available in the public domain or to competitors, what technological components it involves, and whether these are emerging or mature technologies. Detailed comparisons and benchmarking to industry standards can help raise awareness of core competencies. SMEs should combine analyzing activity and knowledge type with the outsourcing matrix to understand their unique value propositions. For example, an SME might be in a mature industry with widely available product knowledge but have implicit organizational knowledge linked to its potential SO activity. In such a case, even if the activity seems ideal for outsourcing from one perspective, the SME should reconsider the advantages and disadvantages of SO.

When small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) define the decision elements for identifying strategic outsourcing (SO) activities, they should consider variables that consider current and future market situations. It is crucial to monitor market dynamics and filter innovations so that SMEs can survive even if their industry faces collapse due to new emerging technologies. In this regard, an external consulting firm can provide macro-level indicators for a given industry.

Kathleen (1995) also suggests that SMEs should consider the scope of the SO project and the functions it will affect. Even if the company shuts down a complete department with no plans to reinstate it, they should pause and reconsider how this will impact the rest of the organization to understand the SO decision’s effects on the company’s team spirit and retain unique talents.

Considering the overall effect is especially critical in knowledge and activity transfer, as managers need to define the scope and effects of SO across the entire entity rather than limiting it to one department or production line. For example, if the team responsible for knowledge transfer knows they are being made redundant, individuals may intentionally ignore or even undermine the transfer. They might take actions such as not mentioning certain practices in their process documentation or excluding important information from records, feeling victimized by the company’s decision to lay them off (Kathleen 1995) (Lorber 2007).

Evaluation of SO project. Go or No Go?

The research by Baloh et al. (2008), Elango (2008), and Hamel et al. (1989) indicates that companies should conduct benchmark analyses after identifying potential activities for outsourcing. These analyses help companies identify the gaps in their current activities compared to their competitors and determine if improvements can be made internally before outsourcing. This process helps the company establish achievable goals for the project. Clearly defining the company’s goals also assists in selecting an outsourcing partner capable of meeting the company’s performance targets.

SO evaluation is more than a Fix Cost Calculation

When evaluating activities for potential outsourcing, companies often focus on operational costs. However, other factors must be considered for a realistic understanding of viability (Hamel et al. 1989) (Elango 2008). Today’s business environment demands flexibility, and companies can achieve this through outsourcing (Quélin & Duhamel 2003) (Elango 2008) (Harland et al. 2005). Outsourcing can provide benefits such as economies of scale, accessing external knowledge and expertise, and taking advantage of tax shields or geographical differences (Baloh et al. 2008) (Marques & Ferreira 2009) (Ohmae 1989). However, it’s important to note that too much outsourcing can lead to high costs and dependency on the outsourcing supplier (Becker & Zirpoli 2011) (Harland et al. 2005) (Quélin & Duhamel 2003) (Gonzalez et al. 2005). In knowledge-intensive activities, gaining specialist knowledge is a significant reason for outsourcing decisions for SMEs, and freeing resources for strategic innovation is an important consideration for manufacturing firms (Rundquist 2003).

According to Hamel et al. (1989), the risks of SO are mainly related to knowledge management and generation. Companies focus on cost-benefit ratios and accessing new markets, neglecting the need to generate new knowledge. Over time, the supplier can gain more knowledge and enter the same market to compete against the outsourcing company.

Running the SO project centrally is important to avoid damaging the company’s competitive advantage (Hamel et al. 1989). Whitmore (2006) presents several risks, including the transition risk, and emphasizes the need for companies to create an exit strategy to remain flexible during SO.

To address these issues, Kathleen (1995) proposes that companies should take several steps to define the objective of SO before moving forward:

a) Determine what the company aims to achieve

b) Plan the direction of the SO project

c) Establish how these goals are connected to the activity being considered for SO.

In an article by Kathleen (1995), there are additional recommended actions:

First, SMEs should assess the current status of the potential SO activity and create a detailed map showing where it falls short of targets and what internal improvements can be made. An executive suggests this to avoid unnecessary expenses with the SO contractor at later stages. Second, the company should compare current practices to industry benchmarks to identify gaps and develop an action plan. Suppose only marginal improvements are possible under the existing conditions. In that case, the investment of time and resources might not be worthwhile, and companies should consider leaving things as they are and moving on to the next step.

The company should clearly define its improvement goals, such as reducing costs, increasing customer satisfaction, or lowering complaints. It should also create a contingency plan for potential disruptions and consider an exit strategy. This planning is crucial before entering into service outsourcing agreements.

Fix Cost and other Cost Elements to consider

The evaluation of an SO project is crucial for SO activity management. This section will provide more detail about the process, including cost calculation.

Converting fixed costs to variable costs is essential for resource management, as it allows for the reallocation of assets into strategic innovation (Elango 2008, Harland et al. 2005, Quélin & Duhamel 2003). Calculating the costs is not complicated, but it requires imagination and creativity from the SME to make the initial identification. The management needs to thoroughly examine current production and potentially re-engineer or redesign the production line to determine how the company can switch activities from fixed to variable costs. This cost conversion provides real business flexibility and is considered a key success factor and motivation in SO decisions (Harland et al. 2005, Quélin & Duhamel 2003).

This work will not delve into the classic details of unit pricing, fixed pricing, performance-based pricing, or combinations. Instead, it will focus on elements not bound to classic pricing and evaluation techniques to shed light on different aspects of SO projects. SO activities closely related to an SME’s core competencies require broader evaluation than primary and secondary SO activities, where the company is not exposed to a threat to its competitive advantage (Elango 2008).

Kelley and Jude (2005) identified five often overlooked cost elements in SO contracts:

- Process-related costs: Check for hidden subprocesses and compare proposed solutions with existing processes.

- Contracts-related costs: Consider the cost of monitoring SO activity and conflict management.

- Communication-related costs: Allocate resources for effective communication before and during the SO transfer.

- Quality-related costs: Plan for defects, reworks, and complaint management.

- Change-related costs: Consider the impact on employee morale and allocate resources for reorientation and new qualifications. Include change management costs in calculations.

Supplier Selection

Many managers in my business network who are involved in supply chain management have identified key factors that small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) consider when making supplier selection decisions. These factors include cost, quality, flexibility, reliability, reputation, economy of scale, scalability, geographic location, time zone, data security, and confidentiality.

While cost is a crucial consideration, SMEs also need to take into account other criteria such as product quality, reliability, on-time delivery, geographic location (including economic and political stability), willingness to collaborate on new product development, and the supplier company’s standing within the industry and among competitors. Additionally, strategic elements like intellectual property (IP) co-sharing, licensing, and confidentiality are also important to touch points in the supplier-selection process (Harland et al., 2005; Quélin & Duhamel, 2003; Lorber, 2007; Kathleen, 1995; Kelley & Jude, 2005).

Trust and reliability are the most important factors in selecting a service provider (Elango, 2008; Hamel et al., 1989; Marques & Ferreira, 2009). These factors are extensively analyzed in various articles and papers to determine if a potential service provider can fulfill commitments and maintain confidentiality in business dealings (Lorber, 2007).

Kathleen (1995) strongly suggests that companies prioritize long-term relationships over outsourcing based solely on price. The cheapest option is not always the best decision criterion. Data security is crucial for maintaining confidentiality in a long-term relationship, particularly when companies share knowledge and intellectual property for production. Audits should be conducted to ensure that the supplier adheres to the same standards as the SME and complies with local regulations and rules without conflicting with those in remote locations (Harland et al., 2005; Hamel et al., 1989).

When evaluating potential service providers, Elango (2008) recommends selecting firms well-recognized within the industry with an excellent reputation for quality, service standards, and technological capabilities that surpass those of the outsourcing company. This is especially important for outsourcing knowledge-intensive activities, where the SME seeks to benefit from the learning effects of outsourcing activities and partnerships. A reputable and successful service provider can also support the SME’s strategic growth, particularly if the partner has access to networks different from those accessible to the SME.

Kelley (2005) suggests that when an SME seeks a reputable partner, it should also request references from the partner, especially when firms are geographically distant. Companies should also consider time zones to avoid scheduling conference calls at inconvenient hours due to time differences.

When considering geographical distances, this research should better investigate the impact of distances on the learning process to justify the importance of this consideration for supplier selection. Rundquist (2003) conducted a case study of SME companies that outsource their product development and found that companies should pay closer attention to real travel distances rather than simply choosing the best partner in the world. He explains that tacit (implicit) knowledge gained by the supplier company during the project and product development can only be effectively transferred through regular face-to-face meetings between partner companies. A physical meeting cannot be replaced despite the availability of advanced communication tools and systems. Geographical location is crucial, as companies must travel frequently at the beginning and even during the supplier outsourcing (SO) process.

Several other studies also highlight additional reasons for the importance of the supplier’s geographical location, such as the associated risks. Whitmore (2006) argues for the significance of location in his list of key supplier decision points by examining socio-economic and political risks and natural catastrophic risks. His argument appears valid, especially after considering examples from the past two years. Swiss Re (2011) reported, „$218 billion worldwide economic losses from natural and man-made catastrophes last year compared to $68 billion incurred in 2009“. Even though SME operations are not on a large scale, the loss of a supplier can disrupt business continuity, leading to damage to reputation or product lines, which could ultimately force the SME out of business. This emphasizes the need for a contingency plan and an exit strategy.

An SME’s survival relies on its reputation and the quality of its services, with products being a major component of this intangible asset. Therefore, SMEs should pay special attention to the quality of final solutions. The supplier’s capability must be evaluated to determine if it can deliver what is requested and promised (Whitmore, 2006). This evaluation goes beyond a reliability check, as the companies must agree on the quality standards required.

The concept of quality is closely associated with pricing and cost calculation. Companies should understand a supplier’s cost components and how these costs can fluctuate. The duration and commitment of the contract are important. If both sides seek a long-term relationship, they can grow together. Trust, reliability, pricing, location, and the supplier’s reputation should be assessed. Companies should also consider the supplier’s real capabilities, including flexibility, scalability, and innovativeness, to increase competitiveness.

The SME should consider its current position in the market compared to its competitors and its strategic planning for the future. It should monitor potential suppliers‘ reputations and market positions to see if their strategies align. Is the supplier ready to be where the company plans to be in 3-5 years? Are both sides‘ competitive strategies compatible? Strategic fit is considered the most important element in this decision (Kathleen 1995).

Another important criterion is the supplier’s commitment to the partnership (Lorber 2007). The SME should also discuss whether the supplier would work exclusively with them on these products. Can the company guarantee that it will not end up with generic products by ensuring the supplier will not supply the same products to competitors?

SME companies have limited resources and usually specialize in adding value to their customers. Their customer relationships and reputation are based on providing inputs that are timely and up to preset standards at all times. When choosing a supplier, SMEs must ensure they can rely on them to live up to their promises. Failure in this relationship caused by choosing an unsuitable partner can seriously damage the SME’s reputation. This point confirms the importance of supplier reliability and reputation.

Activity Transfer

Madsen (2008) discusses the challenges and uncertainties associated with manufacturing transfer. The author argues that transferring manufacturing operations involves more than just a physical and technological move. The difficulties lie in transferring operational knowledge, as converting this knowledge into an explicit form is problematic and often overlooked in transition management. This section highlights the challenges in managing SO (strategic outsourcing) for activity transfers during the transition period (Madsen et al., 2008).

Kelly (2005) also addresses this issue with an example: „We’ve all known organizations where the individuals running the business have the processes for doing so stored only in their own minds. Imagine one of these indispensable people suddenly unable to work – ‚indispensable‘ instantly becomes a ‚single point of failure.‘ The obvious solution is to document the business process so that others can step in, or an outsourcing firm can take over the work.“

The main reasons for the failure of strategic outsourcing projects are knowledge transfer and documenting existing processes. Many encounter difficulties at any project stage due to situations that were never documented or discussed before, involving tacit knowledge that the parent company accumulated over many years and thus considered business as usual. This becomes particularly problematic when considering cultural differences in daily business operations.

Once process documentation is in place, the challenge of running the transition period arises, including training and educational meetings. A common issue is not allowing enough time or resources for the program. Project managers often set target periods based on calculations without considering operational practices. It’s important to take into account the experience of the operation teams to set a realistic time frame for handing over activities. This should include time for learning the process, practicing it, and shadowing the responsible person in the mother firm (Kelley & Jude, 2005). If existing activity processes are successfully documented, companies can identify improvement opportunities before the activity transfer. This can save money and prevent future issues if the supplier makes the improvements themselves (Kathleen, 1995). Documenting and making improvements also allows companies to consider compatibility with the supplier. It’s a good time to check if the supplier’s solution aligns with the company’s existing operations or data handling systems. This early check approach can make managing and controlling SO activity performance easier in later stages.

When handing over activities to an SO partner, companies must ensure that their in-house teams stay knowledgeable, even if that knowledge comes from the supplier (Hamel et al., 1989). Companies should reallocate their human resources into new departments and use their capabilities further to provide an exit strategy (Lorber, 2007). This helps the company to remain a leader in the activity and developments, preventing loss of competency and market shares (Becker & Zirpoli, 2011).

SMEs should keep resources in-house and collaborate with strategic outsourcing (SO) partners to enhance their knowledge base. They should document current processes and update them for SO activities. If retaining resources becomes impractical, keeping them until the SO project stabilizes to mitigate risks is advisable.

SO Contract Management and Performance Monitoring

The identification of key performance indicators is crucial for controlling SO activities. Coordination and integration of multiple outsourcing partners can become a serious problem if the SME loses track. Different SO partners may develop contradicting solutions, making integration impossible. SMEs are advised to pay special attention to data handling with suppliers, especially if the activity is within its core competency area. It is recommended that companies keep coordination and leadership activities for product development in-house to protect company knowledge and resources.

Learning from the SO Partnership and Knowledge transfer

Communication and regular meetings are crucial for effectively transferring knowledge between companies in partnerships (Rundquist 2003) (Lorber 2007). This is especially true regarding transferring tacit (implicit) knowledge, which can only be achieved through face-to-face interactions and direct involvement in operations (Szulanski 2003). Face-to-face meetings at an operational level with the supplier become particularly important when converting tacit knowledge into explicit information. Although not necessary for all types of activities, this is particularly relevant for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) outsourcing knowledge-intensive activities. Such meetings can facilitate knowledge transfer and help SMEs later bring newly generated knowledge back in-house. Several sources agree that the main purposes of such activities should be to acquire new knowledge (Hamel et al. 1989) and to maintain absorptive capacity (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990) (A Zahra & George, 2002).

In my experience working with activity transfers in a Bratislava service center, I have found that tacit knowledge transfer in both directions was only possible when both parties were directly involved in daily operations and could learn from each other. This kind of learning could not have been achieved through process documentation.

Rundquist (2003) also emphasizes the importance of regular physical meetings for the transfer of tacit knowledge. He identifies two types of tacit knowledge created by the supplier team during the contract: technological knowledge and managerial experience. To enable the transfer, he suggests that partners should be geographically close to each other to allow for regular physical meetings. In his study, regular meetings are also identified as important for controlling the activity and building better relationships between operational teams.

Sharing best practices through a lessons learned approach can facilitate knowledge accumulation. Additionally, utilizing cross-organizational knowledge data handling technologies and establishing a structure around knowledge management can aid in new knowledge creation and building upon existing know-how (Hamel et al. 1989) (Shaker A. Zahra & Covin 1994).

Monitoring of Markets Dynamics

Companies must stay abreast of market trends and dynamics to maintain and grow their market presence. Analyzing new technologies and trends can provide significant advantages over competitors. It’s crucial for companies to effectively manage risks and adapt to changing market demands to remain competitive (Porter 1996, cited by Marques & Ferreira 2009).

Companies require strategies to address market changes and prepare for competition. Simply holding market share is insufficient; companies must sustain competitiveness (Hamel et al. 1989). According to Grant (2008), companies must determine where and how to conduct business successfully.

Answering these questions involves two strategies: corporate strategy, where the company selects industries and markets based on macroeconomic data, and business strategy, which determines how to compete within chosen industries.

The first step in enhancing competitiveness is ongoing monitoring of emerging technologies, changes in customer preferences, legal requirements, and socioeconomic or political variables. Companies also need to keep an eye on existing and potential competitors. Competitors can emerge from unknown territories and industries with unknown technologies, following the theory of creative destruction (Schumpeter 1934, cited by Aghion & Howitt 1990), posing significant challenges if companies are unprepared.

Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) must consider all these factors in their strategic outsourcing (SO) project evaluations, as it involves more than just fixed cost calculations. This study presents existing literature and studies according to the 7 SO management steps. It outlines the motivations and risks of SO and identifies managerial knowledge and suggestions to mitigate them. This study aims to establish a framework for measuring differences in companies‘ approaches to SO management. The research will apply the SO decision model to compare theoretical findings to the practical SO management of SMEs.

Empirical Study

The research aims to identify the differences between small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in their supply chain management practices. Since supply chain management is a broad subject with many variables affecting the process and outcomes, it is important to decide what should be measured and how it should be measured in this study. Choosing the correct empirical study setting, design, and tools was important to ensure reliable and valid results in this work. The steps of this process are explained to show how the study was structured.

Research Design

This study used an exploratory case study methodology to understand how small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) deal with and manage strategic outsourcing (SO) in their industry settings. This method will help us gain practical insights and identify any gaps and limitations in our conclusions.

The study followed the basic steps of a comparison case study as suggested by Yin (2003):

1. Identifying the research problem and the question:

European SMEs face significant pressure due to globalization and the rapid spread of manufacturing knowledge. Strategic outsourcing (SO) appears to be a potential solution to these challenges in the short term. However, there are both benefits and risks associated with SO activities. SMEs need to manage SO activities effectively from the start due to limited resources and capital. The research question formulated from this problem is:

How can SME owners and managers identify and manage the right outsourcing activities and collaborate with their SO partners to generate new knowledge for increasing innovation and competitiveness?

2. Creating a theoretical framework:

Existing studies reveal the motivations behind SO choices and the associated risks. The literature also covers approaches that companies can adopt to mitigate these risks. Several studies explore the factors companies should consider before engaging in SO practices. Examples include making outsourcing decisions with cost factors in mind, considerations before making outsourcing decisions, dos and don’ts for technology outsourcing, collaboration during tough competition, monitoring learning activities, protecting core knowledge in outsourcing partnerships, situations when outsourcing should be considered, and company risk assessments.

Based on the suggestions from the literature, discussions within my business network, and personal experience, 7 key steps in supplier outsourcing (SO) management were identified. If applied correctly, these steps should provide guidance to company managers in their supplier outsourcing decisions.

The 7 key steps are as follows:

- Identification of supplier outsourcing (SO) activities

- Evaluation of SO activities

- Supplier selection

- Activity transfer

- Control and management of SO contracts

- Learning effect and knowledge transfer

- Monitoring of market dynamics and emerging innovations.

These further steps in Yin’s framework are explained in detail later in this chapter:

- Set the limitations

- Select samples

- Prepare for data selection

- Run interviews and collect data

- Analyze the findings

Sources of Data

I researched small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in Slovakia because I have close connections with many. These companies mainly operate in component manufacturing and have faced significant challenges since the 1990s, when they could compete in global markets for the first time. I considered these SMEs part of a moderately changing industry, focusing on meeting customer needs. This market is business-to-business (B2B), where original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) set the rules, and SMEs have little influence. Building a close relationship with OEMs and participating in product co-development activities is crucial for SMEs to stay competitive and meet market requirements.

After the regime change and Slovakia’s entry into the Eurozone, Slovakian companies initially had lower labor costs, attracting European investors and automobile companies. However, after entering the Eurozone, labor costs increased, affecting the competitiveness of Slovakian companies. Many companies have implemented organizational changes (SO) to regain competitiveness, but SMEs lack experience in these practices. They may risk losing their competitive edge in the long run if they fail to invest in human resources and innovation.

In this context, organizational changes seem necessary for companies to meet the demands of their business customers. However, due to the relatively young global knowledge on these changes, companies need more experience to be successful. Many companies lack the resources to afford and learn from mistakes. Therefore, these companies can benefit from the findings of my research.

Sampling and Selection of the Cases

The original intention of the study was to focus solely on small and medium-sized manufacturing enterprises (SMEs) in Slovakia, which were identified through my business network. I gathered over 20 company names for SMEs in Slovakia and visited some at two exhibitions. The first exhibition occurred in Brno, Czech Republic in October 2010, and the second was held in Nitra, Slovakia in May 2011.

During these exhibitions, I identified successful and high-performing companies from the initial list of 20. As financial information was not available at that stage, companies were selected based on their demonstration of innovation and presentation of new products at the exhibitions, as well as their general recognition as successful companies within the sector. Two out of the high-performing companies were present at both exhibitions, showcasing new products at their stands.

A total of 7 companies were selected and categorized into two groups: 3 high-performing companies and 4 average-performing companies. Subsequently, 10 interviews were conducted with 10 different interviewees who were company owners, partners, or decision-makers involved in senior management.

The 3 high-performing companies were selected based on their significant success and growth over the last five years and their innovation and ability to provide new solutions to business customers. Two companies manufacture plastic components, while one specializes in providing welding solutions within the automotive manufacturing industry.

Although the initial focus was on manufacturing companies, the two studied companies have shifted more towards retail and completely outsourced their manufacturing capabilities. It is interesting to explore these companies‘ core business knowledge, their coordination with multiple suppliers, and their survival. Notably, the companies that completely outsource their manufacturing capabilities are part of the average-performing company group.

The 4 average-performing companies were selected based on their inability to enter new markets or increase their market shares over the last five years. These companies have experienced a slight decline in revenue during this period, leading to financial challenges that hinder their ability to attract new customers or meet new requirements from business partners due to decreased capabilities and a struggle to compete on price and delivery.

Two other average-performing SMEs are involved in component manufacturing. One of the companies is an electronic equipment manufacturer, while the other provides maintenance for vending machines and partially manufactures spare parts.

After identifying the successful companies based on the set criteria, I had the opportunity to validate my findings by reviewing each company’s financial data for the past 5 years during the interviews.

However, it’s important to note that company names and financial data must remain confidential. For high-performing companies, this aligns with concerns expressed by interviewees about their competition gaining access to sensitive information. For average-performing companies, it would be inappropriate to publicly reveal that they have experienced declining performance over the years.

Instrumentation and Data Collection

In a multiple-comparative case study, it is crucial to use the right tools to ensure the reliability of data collection and analysis. Therefore, it was important to establish the proper settings for data collection, including a theoretical framework that helped design the SO management model. This model serves as a tool for assessing current SO practices. By defining this model, a standardized measurement scale was established.

The following section will outline the additional steps taken to study the selected SMEs in this observation platform.

A structured interview questionnaire

In a previous literature review, 7 steps in SO management were identified as key focus areas that could help companies overcome challenges associated with SO practice. As suggested by previous studies, I delved into the specific decision-making elements involved in these steps and developed a questionnaire to explore how SO managers implement these ideas in their decision-making processes. This study aimed to assess the approaches of SME companies and their comprehension of these key elements, with a focus on delineating the differences in management approaches to SO using a 5-point scale questionnaire. The questionnaire, consisting of 55 questions across 7 sections, was designed to enable company owners, partners, and SO decision-makers to express their opinions on each decision element. The scaling of the questionnaire was structured as follows:

- Strongly Disagree

- Disagree

- Neither Disagree nor Agree

- Agree

- Strongly Agree

Interviews

The interviews took place in May and June of 2011. Four interviews were conducted in person at a company’s premises, while six were conducted through telephone conferences and an online survey provider. The interviews strictly adhered to a set of predetermined questions to ensure that the discussions remained focused on the topic of SO (presumably „strategic outsourcing“) in daily business and specifically identified companies‘ thoughts on key elements related to SO.

The structured questionnaire was distributed to company decision-makers to gain a realistic understanding of current outsourcing practices and assess the significance of SO within a company. During the interviews, participants were allowed to rate each decision element’s importance and demonstrate their understanding of these elements. In cases where a point was unclear, the background of the question was explained to help the interviewees evaluate its relevance to their SO practices. Furthermore, companies shared their financial status to confirm the assumption that they were either high-performing and successful or had concerns about losing market share. Some companies were facing challenges due to the replacement of their products by new technology or solutions provided by competitors, and they were seeking a competitive solution. Strategic outsourcing was often considered as a means to compete with these rivals.

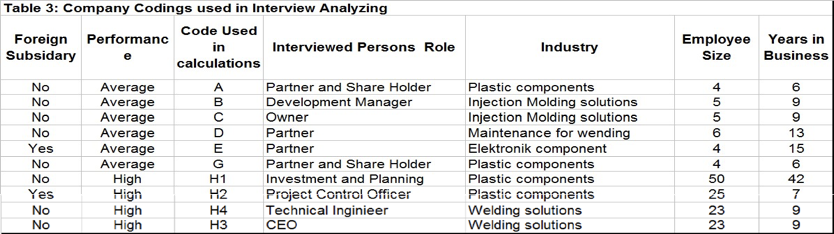

Table 3 presents the general characteristics of the companies studied. To ensure openness and reliability in the companies‘ responses, the names of the companies and their financial data were kept confidential.

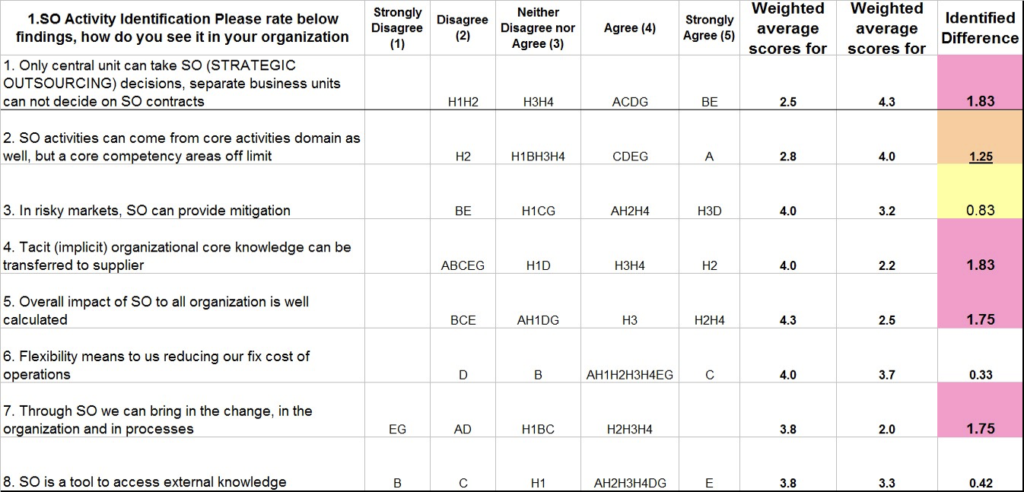

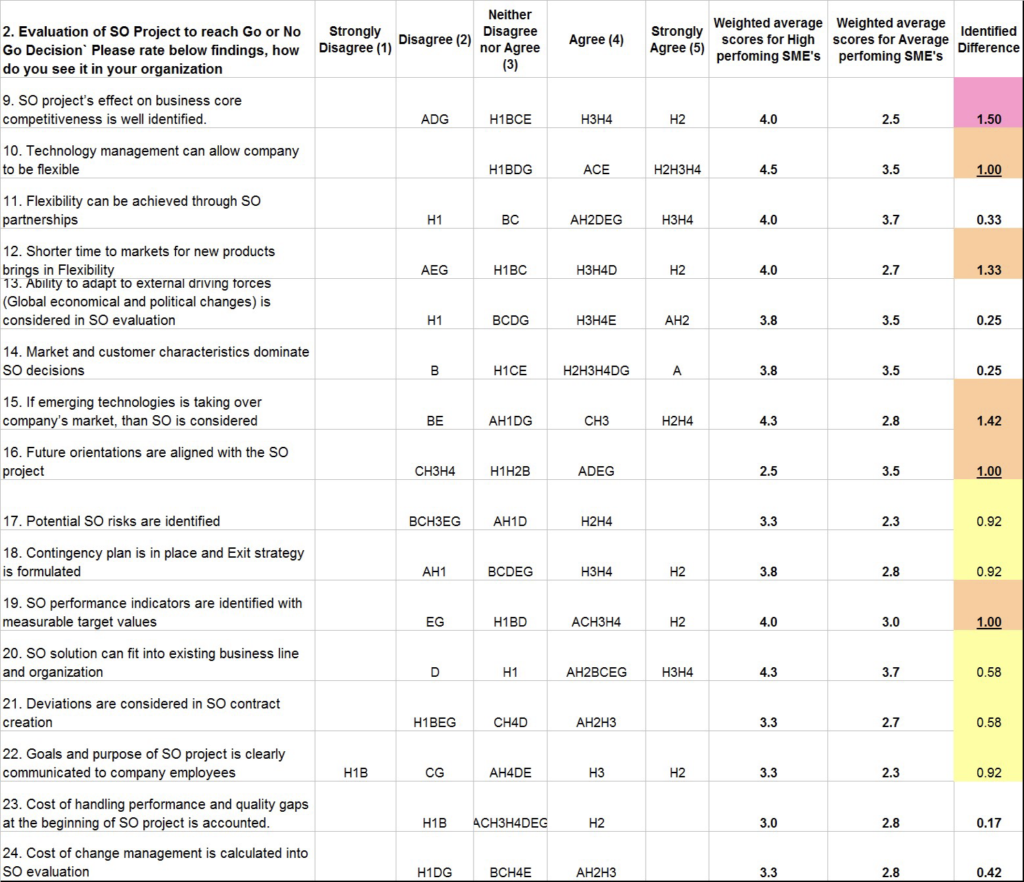

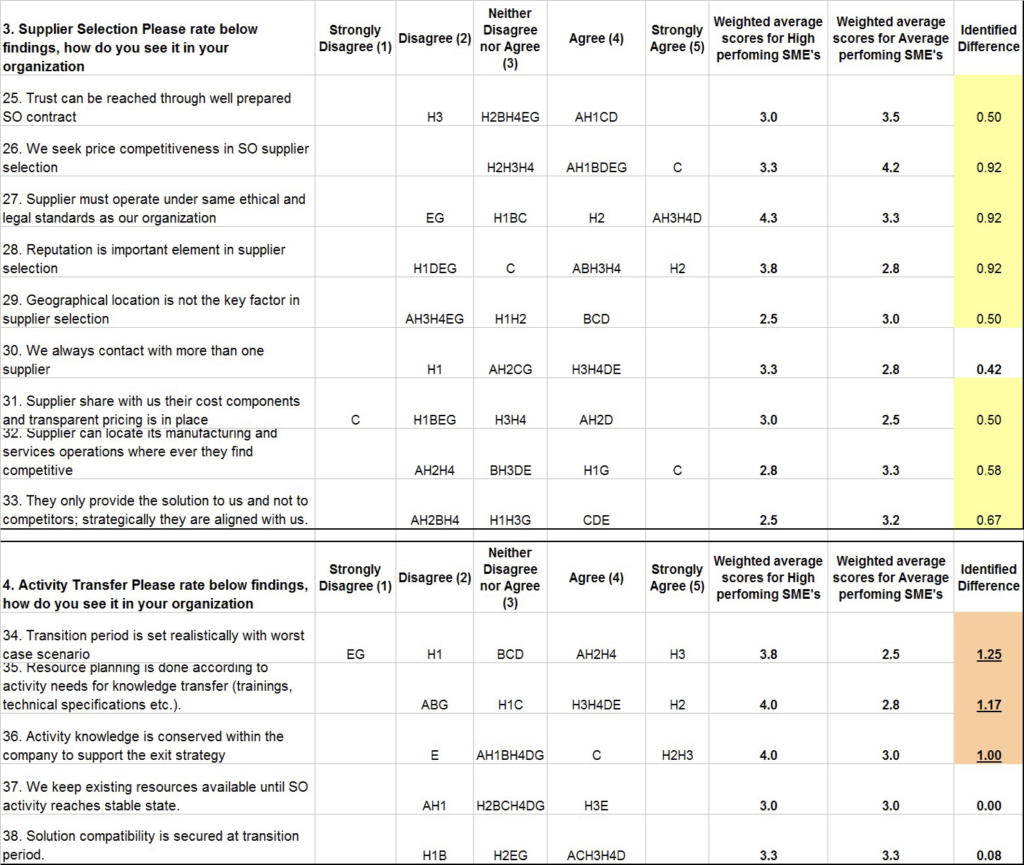

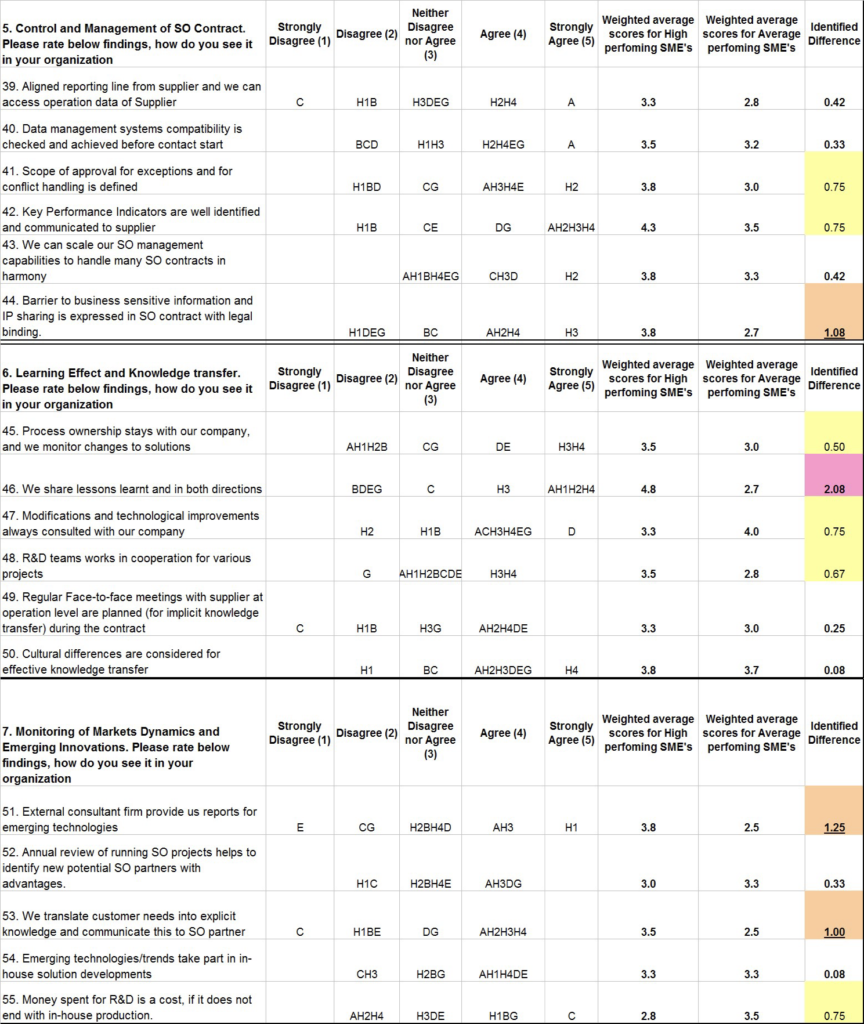

Analysis of the Findings

After conducting interviews, the data was entered into Excel to calculate the average weighted means for both groups in each decision element. This was done to determine if the groups had similar or differing approaches to different elements.

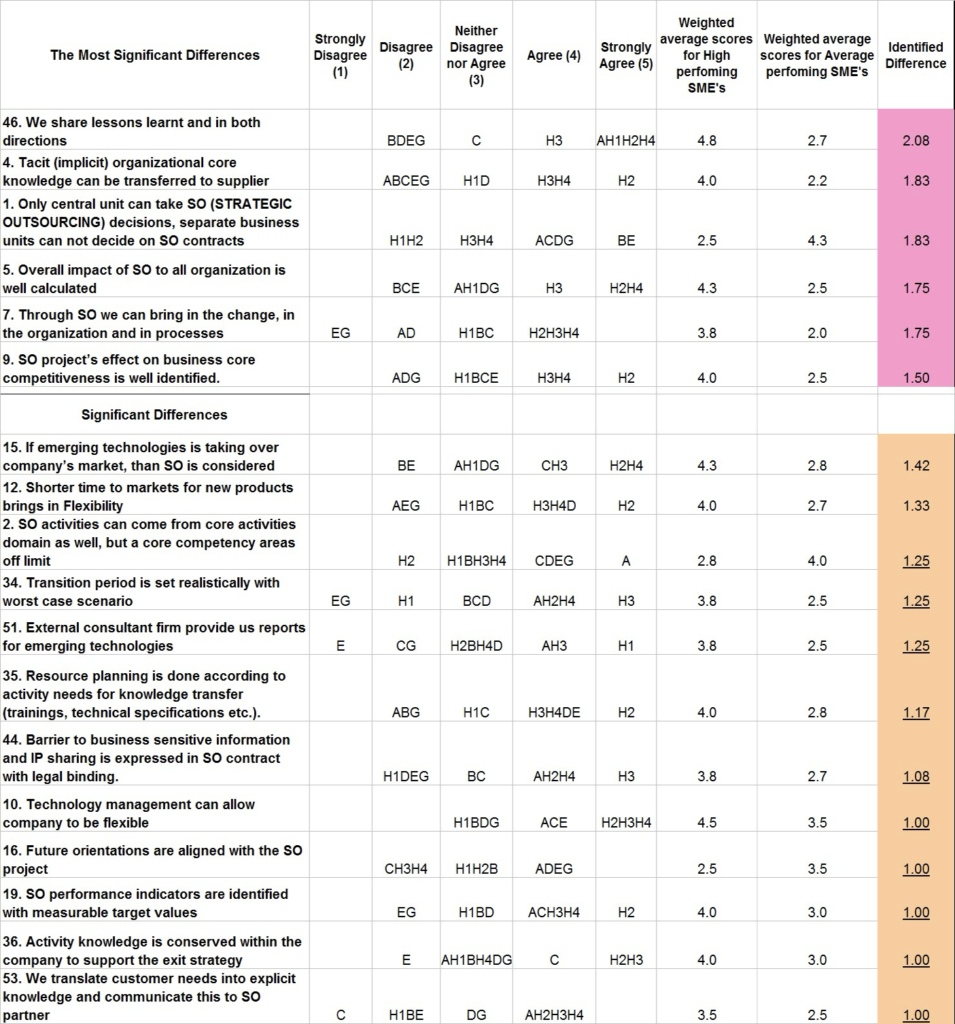

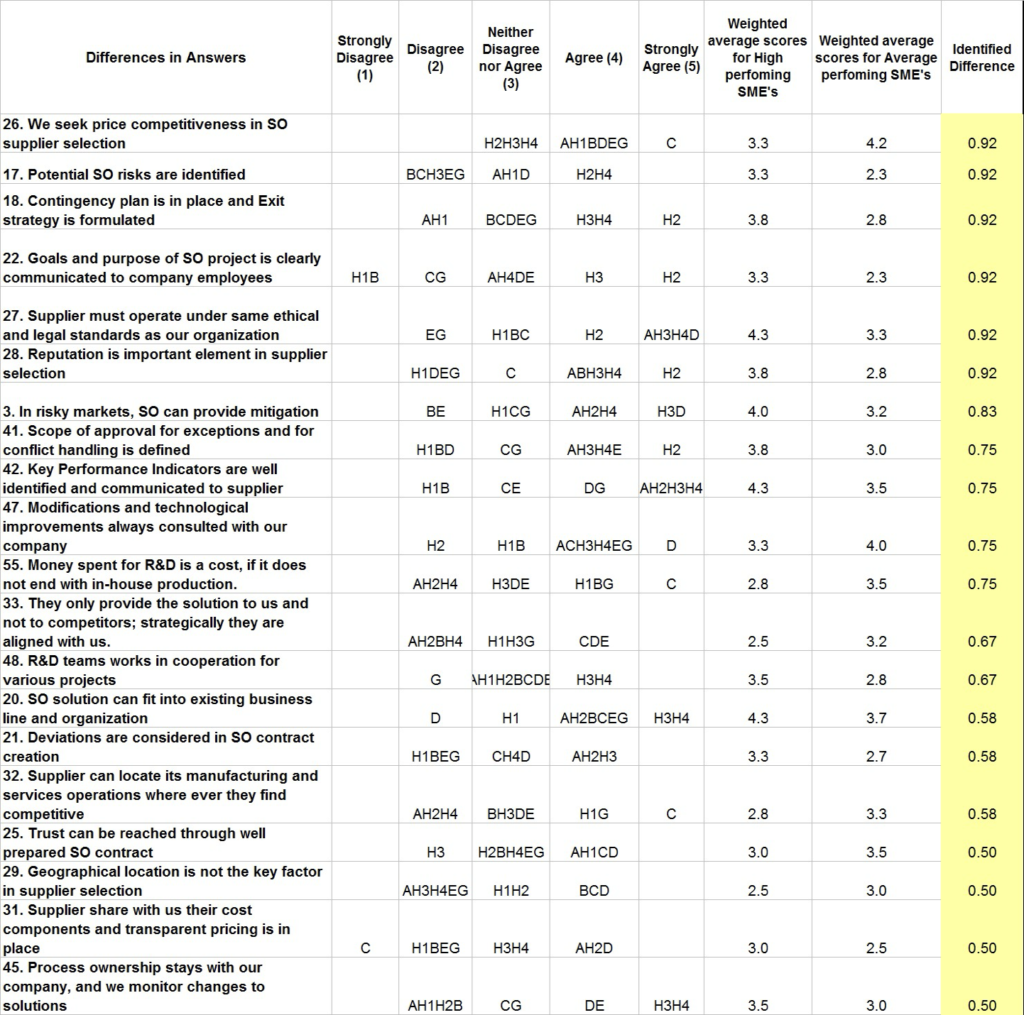

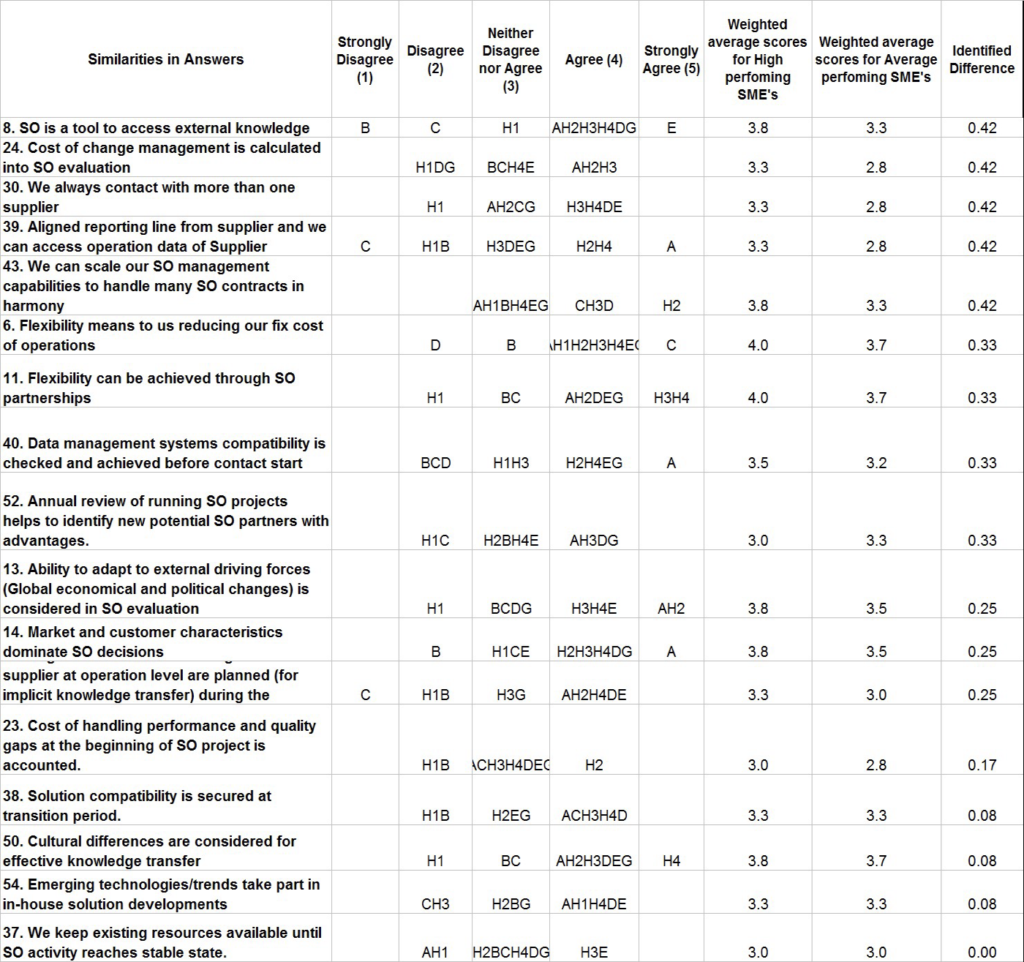

This process allowed us to visualize the differences between the two groups of companies. The findings were grouped into 4 main sections:

- Elements where the practices of the two groups were similar

- Areas where they differed slightly

- Areas where they disagreed significantly

- Areas where they differed most significantly

The classification was based on weighted means of the answers from each group of companies and is presented as follows:

- 0.00 to 0.49 representing similar approaches in SO decision steps

- 0.50 to 0.99 representing different approaches in SO decision steps

- 1.00 to 1.49 representing significant differences in SO decision steps

- 1.50 and above representing the most significant differences in SO decision steps

These four groupings present these findings in Table 1 – Table 3. The results can be seen in Table 5 – Table 7, where the findings are divided into each of the 7 SO decision steps.

Table 1: Results in groupings for the Most and Significant Differences

Table 2: Results in groupings for Differences in Answers

Table 3: Results for Similarities in Answers

Table 4: Interview Results with calculated weighted Averages

Table 5: Interview Results with calculated weighted Averages

Table 6: Interview Results with calculated weighted Averages

Table 7: Interview Results with calculated weighted Averages

Findings from interviews are further presented in the coming chapter in more detail, considering the comments given by interviewees. This was necessary to give greater meaning to the findings to better interpret the presented data.

Conclusion

This empirical study delved into the intricate landscape of supply chain management practices within small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). By meticulously designing the research process and employing an exploratory case study methodology, this study aimed to illuminate the strategies and challenges associated with strategic outsourcing (SO) in SMEs operating within Slovakia’s manufacturing sector. The theoretical framework, anchored in the existing literature and refined through discussions and personal insights, provided a robust foundation for investigating the complexities of SO decision-making.

The research design, meticulously outlined and executed, facilitated a nuanced understanding of how SMEs navigate the intricacies of supplier outsourcing. Through a careful selection of cases comprising high-performing and average-performing companies and a comprehensive data collection approach involving structured interviews, this study captured rich insights into the dynamics of SO management.

This study’s findings revealed converging and diverging approaches to SO decision steps among SMEs in Slovakia. While some areas exhibited similar practices between high-performing and average-performing companies, notable differences emerged, signifying the multifaceted nature of SO management within the SME landscape. These variations underscored the importance of context-specific strategies tailored to SMEs‘ unique challenges and opportunities in their pursuit of competitive advantage. By presenting the findings through a systematic analysis framework, this study offers valuable insights for SME owners, managers, and stakeholders seeking to enhance their SO practices. The delineation of similarities and disparities in SO decision steps is a roadmap for SMEs, guiding them toward informed decision-making and proactive management of outsourcing activities.

Furthermore, elucidating findings in conjunction with interviewee comments enriches the interpretive depth of the study, providing nuanced perspectives on the underlying drivers and implications of SO management practices within SMEs. This holistic approach not only enhances the validity and reliability of the findings but also contributes to the practical relevance of the study in informing strategic decision-making processes. In essence, this empirical study contributes to the existing body of knowledge on supply chain management within SMEs, particularly in the context of strategic outsourcing. By shedding light on the intricacies of SO decision-making and management practices, this research offers actionable insights for SMEs striving to navigate the evolving landscape of global competition and innovation. Continuing research and dialogue in this domain are imperative to foster resilience, agility, and sustainability within SMEs, fostering economic growth and prosperity in local and global markets.

Reference:

Alexander, M. and Young, D. (1996b) Strategic outsourcing. Long Range Planning 29, 116–119.

Alexander, M. and Young, D. (1996b), „Outsourcing: where’s the value?“, Long Range Planning, Vol. 29 No. 5, pp. 728- 0.

Baloh, P., Jha, S. & Awazu, Y., 2008. Building strategic partnerships for managing innovation outsourcing. Strategic Outsourcing: An International Journal, 1(2), pp.100-121.

Barthe’lemy, J. (2001) The hidden costs of IT outsourcing. Sloan Management Review 42(3), 60–69.

Barthe’lemy, J. and Geyer, D. (2000) IT outsourcing: findings from an empirical survey in France and Germany. European Management Journal 19(2), 195–202.

Becker, M. & Zirpoli, F., 2011. What happens when you outsource too much. MIT Sloan Management Review, 52(2), pp.59–64.

Becker, M. and Zirpoli, F. (2003), „Organising new product development knowledge hollowing-out and knowledge integration – the FIAT autocase“, International Journal of Operations & Production Management, Vol. 23 No. 9, pp. 1033-61.

Cohen, W.M. & Levinthal, D.A., 1990. Absorptive Capacity: A New Perspective on Learning and Innovation, Administrative Science Quarterly, March, Vol. 35, No. 1 , pp. 128-152.

Cox, A. (1996), „Relational competence and strategic procurement management“, EuropeanJournal of Purchasing and Supply Management, vol. 2 No. 1, pp. 57-70.

Doz, Y. (1988), „Technology partnerships between larger and smaller firms: some critical issues“,in Contractor, F. and Loragnge, P. (Eds), Cooperative Strategies in International Business,Lexington Books, Lexiington, MA.

Elango, B., 2008. Using outsourcing for strategic competitiveness in small and medium-sized firms. An International Business Journal incorporating Journal of Global Competitiveness, 18(4), pp.322-332.

Ellram, L. and Billington, C. (2001), „Purchasing leveraging decisions in the outsourcing decision“, European Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management, Vol. 7 No. 1, pp. 15-27.

Grant, R.M., 2008. Contemporary Strategy Analysis sixth edition., Wiley page 19.

Greaver, M.F. (1999), Strategic Outsourcing: A Structured Approach to Outsourcing Decisions and Initiatives, American Management Association, New York, NY.

Kakabadse, A. and Kakabadse, N. (2002) Trends in outsourcing. European Management Journal 20(2), 189–198.

Kathleen, K., 1995. 10 things to consider before making an outsourcing decision. Insurance & Technology, 20(2), p.38.

Kelley, M. & Jude, M., 2005. Making The Outsourcing Decision. Business Communications Review, 35(12), p.28.

Khosrowpour, M., Subramanian, G. and Gunterman, J. (1995) Outsourcing organizational benefits and potential problems.In Mamaging Information Technology Investments with Outsourcing, ed. M. Khosrowpour, pp. 244– 268. Idea Group Publishing,

Knight, L.A. and Harland, C.M. (2000), „Outsourcing: a national and sector level perspective onpolicy and practice“, in Erridge, A., Fee, R. and McIlroy, J. (Eds), Best Practice Procurement: Public and Private Sector Perspectives, Chapter 6, Gower, Aldershot,pp 55-62

Lewin, A.Y. & Peeters, C., 2006. The Top-Line Allure of Offshoring. Harvard Business Review, 84(3), p.22.

Lonsdale, C. (1999), „Effectively managing vertical supply relationships: a risk management model for outsourcing“, Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, Vol. 4 No. 4,pp. 176-83.

Lorber, L., 2007. Small Business Link: An Expert’s Do’s and Don’ts For Outsourcing Technology. Wall Street Journal, p.B.8.

Madsen, E.S., Riis, J.O. & Waehrens, B.V., 2008. The knowledge dimension of manufacturing transfers. A method for identifying hidden knowledge. Strategic outsourcing: an International Journal, 1(3), p.198.

Marques, C.S. & Ferreira, J., 2009. SME Innovative Capacity, Competitive Advantage and Performance in a „Traditional“ Industrial Region of Portugal. J. Technol. Manag. Innovation, 4(4).

Marshall, D.J. (2001), „The outsourcing process: from decision to relationship management“,unpublished PhD thesis, School of Management, University of Bath, Bath.

McFarlan, F.W. and Nolan, R.L. (1995) How to manage an IT outsourcing alliance. Sloan Management Review Winter,9–22.

McIvor, R. (2000), „A practical framework for understanding the outsourcing process“, Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, Vol. 5 No. 1, pp. 22-36.

Mowery, D.C. (Ed.) (1988), International Collaborative Ventures in US Manufacturing, Ballinger,Cambridge, MA.

Ohmae, K., 1989. The Global Logic of Strategic Alliances. Harvard Business Review, 67(2), pp.143-152.

Porter, M. (1996). What is strategy? Harvard Business Review, Nov./Dec., 6080.

Quinn, J. and Hilmer, F. (1994) Strategic outsourcing. Sloan Management Review Summer, 43–55.

Rimmer, S. (1991), „Competitive tendering, contracting out and franchising: key concepts andissues“, Australian Journal of Public Administration, Vol. 50 No. 3, pp. 292-302.

Rundquist, J., 2003. Outsourcing of New Product Development-More than supplier involvement. In 10th International Product Development Management Conference: Brussels, Belgium, June 10-11, 2003.

Saunders, C.S., Gebelt, M. and Hu, Q. (1997) Achieving success in information systems outsourcing. California Management Review 39(2),63–79

Schumpeter, J.A., 1934. The Theory of Economic Development. New Yoric Oxford UniversityPress,.,

Sharpe, M. (1997), „Outsourcing, organizational competitiveness, and work“, Journal of Labour Research, Vol. XVIII No. 4, pp. 535-49.

Stanko, M.A., Jonathan D. Bohlmann & Roger J. Calantone, 2009. Business Insight (A Special Report): Innovation — Outsourcing Innovation. Wall Street Journal, p.R.6.

Stein, H. (1997), „Death imagery and the experience of organizational downsizing“,Administration and Society, Vol. 29 No. 2, pp. 222-47.

Swiss Re, 2011. Cost of disasters tripled in 2010: Swiss Re. Available at: http://www.terradaily.com/reports/Cost_of_disasters_tripled_in_2010_Swi ss_Re_999.html [Accessed May 18, 2011].

Szulanski, G., 2003. Sticky knowledge : barriers to knowing in the firm, London ;;Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Teece, D.J. (1986), „Profiting from technological innovation: implications for integration,collaboration, licensing and public policy“, Research Policy, Vol. 15, pp. 285-305.

Uttley, M. (1993), „Contracting-out and market-testing in the UK defence sector: theory, evidence and issues“, Public Money and Management, JanuaryMarch, pp. 55-60.

Whitmore, H.B., 2006. You’ve outsourced the operation, but have you outsourced the risk? Financial Executive,. Available at: http://www.thefreelibrary.com [Accessed May 7, 2011].

Zahra, S. A & George, G., 2002. Absorptive capacity: A review, reconceptualization, and extension. The Academy of Management Review, 27(2), pp.185–203.

Zahra, Shaker A. & Covin, J.G., 1994. The financial implications of fit between competitive strategy and innovation types and sources. The Journal of High Technology Management Research, 5(2), pp.183-211.

AUTHOR

Ümit G. PEKÖZ

Faculty of Management

Comenius University Bratislava

Odbojárov 10, 82005 Bratislava 25, Slovakia

REVIEWERS:

Ing. Jaroslav Vojtechovský, Phd. <jaroslav.vojtechovsky@fm.uniba.sk>

Department of Information Management and Business Systems

Faculty of Management, Comenius University Bratislava

Odbojárov 10, 82005 Bratislava 25, Slovakia

prof. RNDr. Michal Greguš, PhD. <michal.gregus@fm.uniba.sk>

Univerzita Komenského, Fakulta managementu

Department of Information Management and Business Systems

Faculty of Management, Comenius University Bratislava

Odbojárov 10, 82005 Bratislava 25, Slovakia

Digital Science Magazine, Číslo 1, Ročník IX. ISSN: 1339-3782